Vietnam’s Battle To Climb The Global Value Chain

The country earns global factory status but fears it will remain an ‘assembly platform’.

Source: Lien Hoang, Nikkei Asia

Flip over an Apple Watch or MacBook box in the future, and it might say, “Assembled in Vietnam.” The imprimatur of Apple would be a win for Hanoi, which for more than a decade has made a priority of attracting top technology brands like Intel, Samsung and Xiaomi to set up supply chains in the country.

Apple sources AirPods earphones from Vietnam and is testing watch and laptop production. Making those more complex devices would be a badge of success for the country’s manufacturing industry and its determination to join the global electronics supply chain.

Vietnam is already the only economy of its size and development level to have cracked the top six on Apple’s coveted supplier list — the iPhone maker in 2020 sourced from 21 suppliers in Vietnam, up from 14 in 2018.

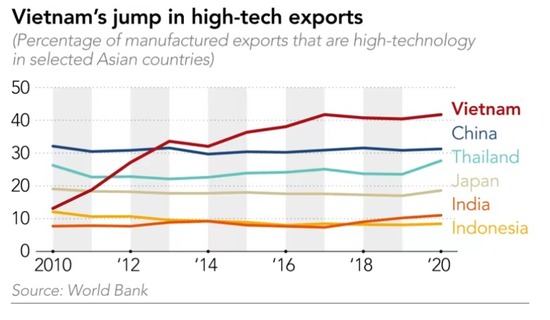

None of those suppliers, however, are Vietnamese. Vietnam’s success in attracting supply chain business — and its failure to create its own domestic high-technology sector — has created a dilemma for policymakers and some curious contradictions in the economy. Vietnam has recorded technology export growth that no substantial Asian rival has matched: High-tech goods as a share of exports hit 42 percent in 2020, up from 13 percent in 2010.

But the country added little value of its own to these exports and has no homegrown tech champions. According to a white paper published by the Ministry of Industry and Trade in 2019, Vietnam lagged most of its Asian neighbors in yardsticks such as trade in value added and manufacturing value added, which measure the contribution of the domestic economy to trade.

Industry leaders express frustration that much of their sector remains a glorified assembly line for other countries’ big brands. Samsung Electronics is another example: the technology giant named only foreign companies among the 25 in Vietnam on its 2020 top suppliers list, despite operating in the country for 14 years and relying on it for half of its smartphone shipments.

“You have something called the glass ceiling. It’s very difficult to break through that ceiling,” the ministry’s multilateral trade director Luong Hoang Thai said, referring to Vietnam’s efforts to advance up the global value chain.

In previous decades, Asia’s “tiger” economies demonstrated that such a journey could be made. South Korea, Taiwan and China all started from low-tech manufacturing and advanced steadily to cars, semiconductors and robots. Indeed, Vietnam has many of the advantages those countries did: a disciplined workforce, low costs and a state industrial policy. But Vietnam lacks some critical elements such as skills and good infrastructure.

“Even though many of the East Asian countries try to follow this kind of model,” Thai said, “very few have been successful, going all the way toward the stage of innovation.”

Meanwhile, it is not clear whether the progress made by the previous generation of Asian economies is even possible today, with the global economy transformed by decades of falling tariffs, and China’s manufacturing dominance. Globalisation may be entering a new and profoundly unpredictable phase as industrial policy makes a comeback and the world redraws trade lines due to supply-chain instability, skepticism of globalism and geopolitical competition.

Vietnam’s trade role has vaulted into a national debate, to the extent that is possible in a state that stifles speech. Some say it’s been slow to enact a clear strategy, such as pushing priority industries to locally source a certain percentage of components, while others say its day is yet to come.

“Before, we hated capitalism,” said Tran Dinh Lam, director of the Center for Vietnamese and Southeast Asian Studies, arguing Vietnam needs time to catch up, having only ditched its planned economy model in the 1980s. “And then we opened the door and we welcomed everyone.”

Economist Phung Tung, Director of the Mekong Development Research Institute, said success would mean that trade benefits most of society, and companies in Vietnam become competitive manufacturers like China’s Oppo or Malaysian chipmaker Silterra, two recent arrivals to the technology sector. But in a parallel dimension failure would, a local institute says, doom Vietnam to be “forever stuck as an assembly platform,” plagued by congestion, stagnation, inequality, or Argentina-style debt crises.

To avoid this middle-income trap, Tung said Vietnam must find its spot in the world’s new strategic trade game.

Promising First Steps

Due south of Hanoi, skyscrapers swiftly give way to fields where water buffalo graze and shirts act as scarecrows. Drive an hour out, and the skyline changes again, in Ha Nam, a once-rural province known for communist revolutionaries and sixth-century folk dances.

Now, though, industrial parks have supplanted marshland, a haven for foreign tech companies that have come to redesign their supply chains. Tenants include Apple supplier Wistron, Seoul Semiconductor, and Anam Electronics, which exports JBL Bluetooth speakers and Yamaha sound systems. Interest in Vietnam as a factory center has risen in line with trends north of the border three hours away.

In the past decade, wage inflation in China’s southern coastal manufacturing centers priced out many suppliers, who then sought to shift production to lower-wage Vietnam.

More recently Vietnam has been the beneficiary of much bad news. First, the U.S.-China trade war, which pushed American companies (along with many Chinese companies) to move suppliers to Vietnam in an effort to escape sanctions. Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, when lockdowns in China hastened more companies — including Apple — to shift production out of China and toward Vietnam.

When shutdowns raised costs to ship goods out of China, for example, Anam turned to a subwoofer speaker producer in Vietnam. In Ha Nam, the South Korean company’s factory contains a rainbow of smart speakers, circuit boards fill an entire room and bots ferry parts between workstations.

“[Vietnam] has been doing well so far by attracting investment,” Anam Vietnam Director Park Hyeon-su said. However, if the country does not upgrade to complex products, it risks a “vicious cycle of technological decline, environmental pollution, low labor productivity, high energy consumption and low efficiency.”

The Vietnamese economy more than doubled in size from 2010 to 2020, according to the World Bank. But the country has a limited window to take advantage of the explosive growth. “The low-hanging fruit of industrialization is to capitalize on your endowments, which is cheap labor,” Natixis economist Trinh Nguyen said.

For Vietnam, she added, “that is set to disappear.”

In other words, if wages increase, companies that currently find Vietnam hospitable might eventually leave for cheaper countries like neighboring Cambodia. The supply chain industry is fraught with politics that makes investments particularly unstable: Companies might also be drawn away by their own government’s homecoming policies (Japan), or by the desire to “nearshore” next to big markets (Latin America or Africa). Other risks include inbound investment that is low-quality or creates pollution as well as tech advancements that make it costlier and harder for poor countries to move up the value chain.

Localisation is starting to happen with Toyota Motor, one of the most profitable foreign investors in Vietnam. Six of the 46 in-country suppliers were Vietnamese, the automaker’s 2021 sustainability report says. Giai Phong Rubber spent the past two years working to become No. 7 — a goal it achieved in July.

Just over the Red River from Hanoi, GPR workers pump out rubber components for appliances, from LG Electronics vacuums to Panasonic washers, against the hiss of compressors and the acidic smell of latex. Chu Trong Thanh, GPR’s Chief Customer Officer, told Nikkei that the company had “dared to step out of” its comfort zone in the appliance and motorbike industries to make car parts “for the honor of the country.”

“When working with Toyota, they are on another level,” Thanh said, adding that he had adopted a just-in-time inventory system and other tactics to join the Japanese giant’s supply chain.

Too Few And Far Between

Less important than a single company’s capacity, though, is the structure and scale of a manufacturing sector that can accommodate large clients. Amazon, for example, brought in staff to scout suppliers like CNCTech, which said it gave the scouts a tour of its machine parts, molding and assembly plant.

The e-commerce player could buy millions of smart doorbells or Wi-Fi devices a year, but no orders came of the trip, said An Do, director of business development for CNCTech, whose products go into self-lacing Nikes and Sharp headphones.

“The story with Amazon is they want to find or build a community of suppliers big enough to have redundancy,” he told Nikkei, walking around a factory in northern Vinh Phuc province where employees tested internet routers in soundproof rooms while sofa-sized machines punched diodes onto circuit boards. “If later they just have one supplier, the risk for them is very big.”

The Seattle-based Amazon does source some doorbells and cameras from Vietnam, but, An Do said, major purchasing managers want a whole ecosystem to secure their production. In China, for instance, entire villages are devoted to supplying just fabric, silicon wafers, or auto parts. Vietnam lacks such clusters — its supporting industries are more scattered and less integrated into global supply chains.

The country’s programs to develop a web of suppliers are “primitive, cumbersome and highly limited,” such as with matching workshops where business cards are exchanged but contracts not inked, according to a 2020 report by Vietnam’s Institute for Economics and Policy Research and Japan’s National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies.

The joint report recommended models like Malaysia, which published clear tax and other incentives for suppliers, or Thailand, which had 10 technical centers, such as for machinery training. Analysts point to two other ways manufacturers gained capacity in China: developing products for a big domestic market before going abroad and supplying to foreign clients before growing into a major competitor in their own right.

“Even though we have attracted a lot of investment there is a weak linkage between the [foreign] sector and the domestic sector,” the trade ministry’s Thai said. “That’s why you have not seen a lot of spillover impact in terms of technology, management and other skills.”

A Rocky Road Ahead

In its pitch to investors, Vietnam waves single-party stability as well as trade pacts, shipping lanes and low costs in a market of 99 million. But it lacks something like a Taiwanese managerial class, high-value national champions in the vein of Hyundai Motor or Acer, and high-skilled labor to power such corporations. As with much of the economy, the solution is a delicate balancing act: More training will bring these skills but also push up wage costs, which will encourage companies to decamp to cheaper shores.

Vietnam GDP more than doubled in past decade

Support for and training the workforce, on the face of it, should not be much of a problem: One of the rare countries run by a workers’ party, Vietnam has labour protections from paternity leave to pensions for freelancers. But can an authoritarian state that brooks no criticism also foster the problem-solving and critical thinking that high-skilled work demands?

That is hard to do in a society that discourages people from questioning authorities, from teachers to officials, said Ha Dang, founder of fair-labour consultancy Respect Vietnam. She added there is a dearth of substantive training to benefit workers long-term.

“Many companies like employees who do what they’re told, they like discipline,” she said in an interview.

But the perennial complaint among bosses is their struggle to hire creative and self-directed staff. Managers, professionals and technicians comprise 10.7 percent of Vietnam’s workforce, the lowest in Southeast Asia’s six big economies, according to the International Labour Organisation.

The next gripe from investors is logistics costs eating up margins, equivalent to 20 percent of gross domestic product, compared with an average 12.9 percent in Asia and 10.8 percent globally, according to a 2021 report from business research firm Vietnam Industry Research and Consultancy.

Land transport claims most of the cost, though highways are less than 5 percent of roads, the report said. Congestion and disrepair are rife, as Vietnam struggles with major projects: a north-south expressway; a second airport for Ho Chi Minh City; and the country’s biggest port, planned for the city.

Construction is slow, requiring 166 days for a permit, versus Asia’s average of 132.3 days, says the World Bank’s Doing Business 2020. More recently, Russia’s war in Ukraine and China’s COVID lockdowns have hit supplies from wood to steel.

These compound Vietnam’s older problems, delaying infrastructure: red tape, bad project forecasts, and land disputes, which can turn violent, most infamously in the deadly Dong Tam standoff between police and villagers in 2020. The Sydney-based Global Infrastructure Hub forecasts Vietnam will spend $503 billion on infrastructure by 2040, but needs $605 billion.

If civil servants were afraid of getting in trouble for approving risky projects before, they have more reason to fear now under an intensifying graft crackdown, which has seen officials jailed for “economic mismanagement causing losses to the state budget.” One developer described it in the lexicon of investors: “There is no upside for the bureaucrat, there is only downside risk.”

So construction timelines are stretched by Kafkaesque minutiae, from forms signed in the wrong ink color, to disagreement about which agency must give approval.

Can You Repeat The Past?

Vietnam is not alone in its 21st-century trade struggles: Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia are not the new South Koreas, either. One question some economists are asking is whether the success stories of a previous century are repeatable in the new one.

From the 1960s Seoul and Taipei took a strategic approach to the global economy. They designed specific industrial policies, erected trade barriers, educated their workforces and picked winners that grew into export giants. They did so, however, in another era. Vietnam today has been able to replicate some of South Korea’s and Taiwan’s export success, but key differences make for an uncertain road ahead.

The country also has massive competition its forebears did not: China. In addition, globalisation has been on the march for decades now, eliminating the ability to erect the kind of tariff barriers that helped early movers like Sony gain an advantage. The global playing field that now exists makes it difficult for Vietnam to use similar protectionist policies to foster its own export giants, economist Phung Tung says.

“The big difference in my mind is in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when China really entered a phase of rapid growth, the size of the tradable sector had grown tremendously, facilitated by low-cost container shipping,” Harvard Business School professor Willy Shih told Nikkei. That made bids by “countries trying to move up the value chain much harder, because they had to compete with a flood of cheap Chinese goods.”

Taiwan and South Korea became democratic advanced economies when offshoring was entering the nomenclature and before the World Trade Organisation slashed tariffs. Xuan Nguyen, an economist at Australia’s Deakin University, estimates import taxes went from 20 percent in the 1980s to 5 percent before the trade war. Vietnam currently has 15 trade deals.

“It’s really tough now,” said Tung. “In the past, each country could use policies like tax or non-tariff barriers to protect companies. But you cannot do that now.” And with more multinationals from Tesla to Toshiba than ever, “It’s really hard for the new one to enter the market.”

Xuan Nguyen said that multinational corporations are further cementing the advantage they gained when their home countries industrialized decades ago, such as by filling their factories with ever-improving tech like robots and seamlessly moving production across borders by hiring contract manufacturers. “The landscape [of] globalization,” he said, “has changed dramatically between the 1980s and nowadays.”

Yet Vietnam is making progress, Tung said. Samsung is planning a research center and to start producing some semiconductor parts in the country. Investors consider these and Apple’s decision to make Apple Watches in Vietnam harbingers that more sophisticated manufacturing is in the cards.

While Malaysia has a stronger supply chain for electronics and Thailand for cars, the countries have “been hobbled by lack of vision due to volatile domestic politics,” Natixis’ Nguyen said, adding that the situation gives Vietnam a chance to surpass its neighbors if it is strategic.

Back at the internet-devices factory, An Do of CNCTech hopes the country embarks on such a course before pollution and old age take over. The workforce is young, but seniors’ ranks are growing: Vietnam is in the top 10 of countries with the fastest-growing dependency ratios.

“We are developing the economy,” he said, slipping on an orange jumpsuit needed to enter the sanitized factory. The investment influx is “good in the short term, but if we don’t make use of it, it becomes a burden. We in Vietnam need something more radical.”

What You Missed:

Metalworking Fluids Market Outlook By Industries And Areas

New-Vehicle Market Expands For Third Straight Month

Semiconductor Industry to End 2022 in Loss! Can Chip Makers Manage?

Investment Opportunities For Saudi Businesses In Indonesia

Rockwell Automation Identifies India’s Digital Prowess, Propels Smart Manufacturing Ambition

China Evergrande’s Unit Starts Mass Production Of First EV Model

Faccin Ensures A Successful Rolling System For CS Wind Malaysia

A Rising Star In CNC From China

ISCAR Explains The Importance Of The Right Tool In CNC Technology

Sustainable Metal Cutting: For People, Planet And Profit

WANT MORE INSIDER NEWS? SUBSCRIBE TO OUR DIGITAL MAGAZINE NOW!

CONNECT WITH US: LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter

Letter to the Editor

Do you have an opinion about this story? Do you have some thoughts you’d like to share with our readers? APMEN News would love to hear from you!

Email your letter to the Editorial Team at [email protected]